|

|

| John Frederic Daniell (1790-1845) was born

in London and took his first job at a sugar refinery and resin factory.

After hearing William T. Brande’s lectures on chemistry, he

was inspired to start his own research. In 1831, he was appointed

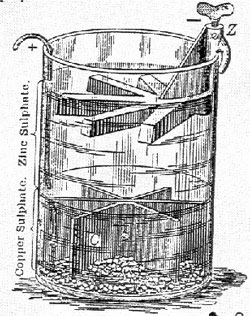

professor of chemistry at King’s College, London. Daniells’s research into development of constant current cells took place at the same time (late 1830s) that commercial telegraph systems began to appear. Early telegraph messages were brief and traveled short distances. Crude, weak batteries were sufficient to support the signal. With the increase in traffic and introduction of Morse sets, stronger currents and more constant output were required in the batteries. Daniell’s copper-depolarized battery (1836) and Grove’s nitric acid depolarized cell were fortuitous arrivals. British and American telegraph systems used the Daniell cell exclusively, as it was the only one capable of being rapidly depolarized. His cells also produced a more constant output and generated a stronger current than Sand batteries. This was the “pre-volt” period, when the intensity of pain was used as a measure of a cell’s power. In 1839, Daniell experimented on the fusion of metals with a 70-cell battery. He produced an electric are so rich in ultraviolet rays that it resulted in an instant, artificial sunburn. These experiments caused serious injury to Daniell’s eyes as well as the eyes of spectators. Ultimately, Daniell showed that the ion of the metal, rather than its oxide, carries an electric charge when a metal-salt solution is electrolyzed. Daniell was a friend and

admirer of Michael Faraday and in 1839 he dedicated his book “Introduction

to the Study of Chemical Philosophy” to him. |