|

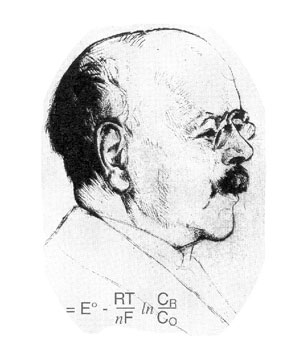

| As a young man in Prussia, Hermann Walther Nernst (1864-1941) expressed his ambition to become a poet. In 1883, he had graduated first in his class at the Gymnasium of Graudenz (currently part of Poland), where his studies focused on classical literature, humanities and natural science. Thirty-seven years later, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for chemistry in honor of his work in chemical thermodynamics. The man who adored the words of Shakespeare created poetry of a different meter when he bridged the quantum theory of Planck with the dynamics of chemical processes. Walther Nernst was the son of a civil servant. He studied in Zurich, Wurzburg and Graz. At Graz, he worked with von Ettinghausen, with whom he published work in 1886 which formed part of the experimental foundation of the modern electronic theory of metals. He took his Ph.D at Wurzburg, beginning his career as a physicist. His transition to chemistry began in Leipzig but developed fully in his subsequent position as an associate professor of physics of Gottingen. In 1905, he was appointed professor of physical chemistry in Berlin. He became director of the Physikalisch-Technisches Reichsanstalt in 1922 and finally professor of physics at Berlin in 1924 before retiring in 1933. Nernst’s first outstanding

work was his theory of the electromotive force of the voltaic cell

(1888). He developed methods for measuring dielectric constants

and was the first to show that solvents of high dielectric constants

promote the ionization of substances. Nernst proposed the theory

of solubility product, generalized the distribution law, and offered

a theory of heterogeneous reactions. In 1906, his heat theorem became

the Third Law of Thermodynamics. This theorem garnered the Nobel

Prize but his research encompassed a far broader scope, including

photochemistry, electrochemistry and studies of high temperature

gases. |